LA Water District paid $42,942 for a single employee’s health insurance plan

Executive Summary

The price of health insurance in America has consistently risen faster than the rate of inflation and, despite the intentions of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), is projected to continue to do so for the foreseeable future. A provision of the ACA known as the ‘Cadillac Tax’ is designed to discourage employers from purchasing excessively priced health insurance plans; which is intended to reduce at least one of the factors that contribute to the dramatic increase of price. This paper draws on a wide array of research that demonstrates government employers are most likely to be affected by the ‘Cadillac Tax’ due to their propensity to purchase the most expensive forms of health insurance available for their employees. A particularly striking form of excess – a $42,942 plan – for an employee of a small water district in Los Angeles County prompted an inquiry into the health costs for other public agencies in the County. This analysis reveals that the largest Los Angeles County public employers are paying approximately 71% more for their employees’ health insurance than private employers, at an estimated cost of $676 million a year.

Introduction

Despite the warning from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) of the impending burden to state and local governments from rising healthcare costs, many Los Angeles governments are purchasing wildly exorbitant health insurance for their employees, at taxpayers’ expense.

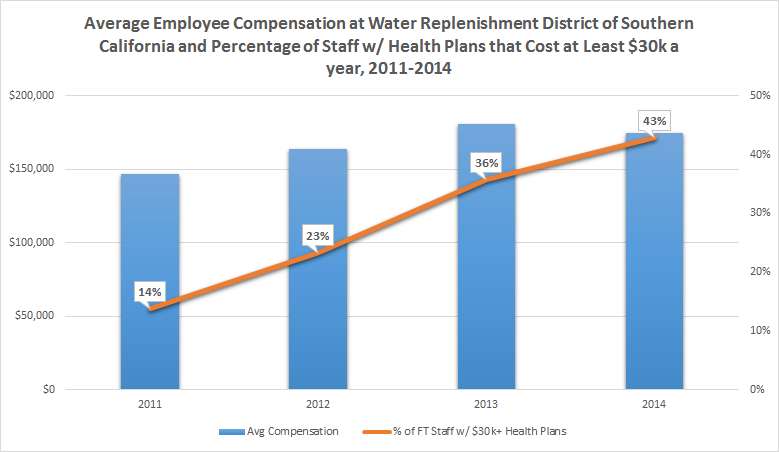

Last year the Water Replenishment District of Southern California (WRD) paid $42,942 for a single employee’s health insurance plan. Nearly half of the District’s full-time employees received a plan that cost at least $30,000 apiece.

In 2011, the WRD had four employees receiving plans that cost at least $30,000. By 2014, that number increased three-fold, demonstrating the $42,942 plan is not a remote outlier, but part of an agency-wide practice of vastly overpaying for health insurance.

Surprisingly, WRD employees are also part of the coveted “3% @ 60” pension plan – which calculates the retirement benefit by multiplying the number of years worked by 3 percent, and then multiplying that number by the employee’s highest salary.

Typically, plans with the generous 3% multiplier are reserved for police and fire employees. In fact, the 3% plan is so expensive that the Pension Reform Act of 2013 eliminated it completely for new hires. New employees at the WRD would be under the reduced, but sustainable, “2% @ 62” formula.

The total compensation package for WRD employees is quite generous as well – full-time WRD employees received an average $180,636 in 2013.

As the data available on TransparentCalifornia.com is making clearer, it is in the often-overlooked smaller, local government agencies where the most dramatic levels of excessive public compensation can occur.

Table 1: Water Replenishment District of Southern California Employee Compensation

The problem is widespread

Unfortunately, California governments overpaying on health insurance goes well beyond the WRD. Transparent California previously reported on the numerous $20k+ health plans in Corte Madera and the Contra Costa Community College District, as well as the $30k+ plans found in the cities of Beverly Hills and Sierra Madre.

Pew Research confirms that the problem is nationwide – over the past 25 years, state and local government spending on health insurance increased 447% in inflation-adjusted dollars, and is projected to rise further.

This dramatic increase can be attributed, in part, to government wastefulness – government employers not only purchase the most expensive plans, they also ask their employees to contribute the least to help fund them.

In California’s public sector, this problem is accelerating at an alarming rate. From 2011-2013 the amount spent on health insurance by the State increased by 8% as compared to the average 1% decrease nationwide, according to Pew Research.

While the WRD’s excess is the highest in absolute terms, its impact is limited due to their small size. As such, it is more meaningful to analyze the larger districts in the state.

This analysis will incorporate data from the State of California and the largest government agencies in Los Angeles County – home to both the largest city and county in the state.

Table 2 compares two of the biggest special districts – the Los Angeles County Sanitation Districts and the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California – as well as the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, the City of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles County government.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides comparable information for private employers. However, the information is only reported by geographical region, not individual state. As such, the Pacific regional data, of which California is the largest component, is used in this comparison.

The BLS data is by coverage type only. Therefore, the average employer cost is estimated assuming a 50/50 split between employees selecting single or family coverage plans, consistent with the trend found by the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Table 2: Average Employer Cost of Health Insurance

Consistent with the nationwide data, Los Angeles governments pay significantly more for health insurance than the average private sector employer.

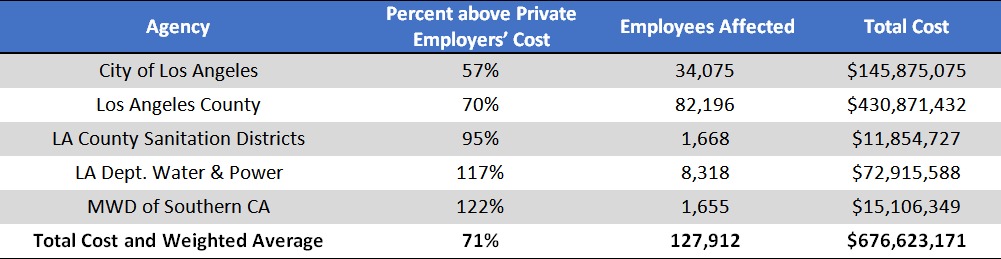

For just the five Los Angeles governments analyzed, the total amount paid in excess of the average private employer’s cost is approximately $676M, as shown in Table 3 below.

Table 3: Average Public vs Private Cost of Health Insurance and Total Cost of Public Excess, Los Angeles

A bad problem gets worse

The forthcoming ‘Cadillac tax’ provision of the Affordable Care Act is expected to pose a significant burden to government employers – due to their propensity to purchase Cadillac-style plans for their employees. Beginning in 2018, employers must pay a 40 percent tax on the excess of plans that cost more than $10,200 for single coverage and $27,500 for family coverage.

It must be noted that the threshold for the Cadillac Tax applies to the total cost of the plan. The values reported here are only the employer costs. If employees also contribute towards the cost – meaning the total cost is higher than just the employer’s share – the number of plans affected will rise significantly.

The WRD, for example, will have to pay at least $41,000 a year in penalty taxes for just the twelve employees with health care plans over the $27,500 cap at their current rates. Virtually the entire full-time staff – over 1,400 employees – of the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California received health plans that cost more than $10,200; if any of those plans are for single coverage only, they would be hit by the tax too.

Los Angeles County had 56,366 employees – about 67% of staff – who received health insurance that cost at least $10,200. Outside of the WRD, the County had the greatest individual cost – with 192 plans costing $37,148 each. For just these 192 employees, the County would have to pay a penalty tax of at least $740,966 a year beginning in 2018.

Given the recent, and projected, double digit increases in health insurance premiums, merely holding costs to the present level by 2018 would be a remarkable feat.

Finally, the City of Los Angeles appears best positioned to avoid being affected by the tax. In addition to having the lowest average cost, there was not a single plan with a cost of more than $16,400.

Conclusion

The increasing cost of healthcare is certainly much more complex than merely being the result of government wastefulness. A comprehensive solution would require an entire rethinking of how healthcare should be provided. Still, having a consumer as big as government routinely overpay for a product will contribute to its rising cost.

As taxpayers are struggling to pay their own health insurance premiums, government should be doing all it can to rein in costs. As bad as the healthcare situation is at the moment, there is simply no justification for a government agency to consistently pay over $20,000 a year, or more, for their employees’ health insurance.